Moving

25 01 2010Paul B. has done something splendiferous and brain-splitting. It is called edwardgauvin.com, and features placeholder copy from his magic tattoo. As a result, this blog will be discontinued: it will remain up indefinitely, but henceforth all new posts will appear here. This move is a fitting digital analogue, so to speak, to the physical move I just made across the country, in his company, in this:

He has also generously moved all past posts from this site so that they are available for viewing at the new site. We did not have to drive these across the country.

Goodbye! See you at the new place!

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized

When the brilliant twenty-year-old chemist

25 01 2010Humphry Davy discovered the potency of nitrous oxide, “laughing gas,” at the recently founded Pneumatic Institution in Bristol in April 1799, he inhaled the new mind-altering substance himself, and shared it with his friends. These included Samuel Taylor Coleridge, already, in his mid-twenties, hiding a growing opium addiction, who noted that he felt “more unmingled pleasure than I had ever before experienced.” The poet Robert Southey, a youthful radical who would later become a conservative-minded poet laureate, also experienced “a sensation perfectly new and delightful,” adding that “the atmosphere of the highest of all possible heavens must be composed of this gas.”

~ Jenny Uglow, “Romantic Scientists” (review of The Atmosphere of Heaven: The Unnatural Experiments of Dr. Beddoes and His Sons of Genius by Mike Jay in the NYRB)

The Atmosphere of Heaven: The Unnatural Experiments of Dr. Beddoes and His Sons of Genius

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized

In another passage of his lecture

23 01 2010bearing on the dialectic of the foreign and the domestic, Schleiermacher argues that the ideal translator is not one who has mastered the foreign language so fully that that he is completely at home in it. Such a translator, he suggests, can produce in the reader an impression of the text that resembles that a native speaker of the language would have—that is, one in which the text seems natural and familiar. But the best translator, Schleiermacher maintains, is one who is never fully at home in the foreign language, and seeks to evoke in the reader an experience like his own, that is, the experience of someone for whom the foreign language is simultaneously legible and alien. Schleiermacher’s ideal translator operates in the space between languages and cultures, between the domestic and the foreign—for only by contrast with the domestic can the foreignness of the foreign be maintained. Like the reader/writer in Roland Barthes’s The Pleasure of the Text, he commutes between the secure pleasures of the familiar and the seductive bliss of its destruction…

…Schleiermacher claimed that there are only two methods of translation: “Either the translator leaves the author in peace, as much as possible, and moves the reader towards him; or he leaves the reader in peace, as much as possible, and moves the author towards him.”

~ Steven Rendall, “Changing Translation” (review of Lawrence Venuti’s The Translator’s Invisibility in Comparative Literature)

I done gone and stuck my nose in other people’s blogs, then opened my big mouth, briefly entertaining a discussion on related themes with fantastical writer Ekaterina Sedia in the comments section to one of her recent posts.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized

Health is the last

23 01 2010emergent post-Christian religion. Dr. Bernard Nathanson, the former abortionist who is now a leader of the pro-life movement, remarks that modern man seeks “somatic immortality” instead of God. This obsession with Nautilus machines and herbal tea was anticipated by Nietzsche, who predicted that the further man got from the supernatural, the more preoccupied he would be with health. The more Nietzsche himself turned against God, the more obsessed he became with the smallest details of his diet and physical tone. (“No meals between meals,” we read in Ecce Homo, “no coffee: coffee spreads darkness…”)

~ George Sim Johnston, “Break Glass In Case of Emergency”

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized

Everywhere the surrealists

22 01 2010left their visiting cards: ‘Parents! Tell your children your dreams.’ The Bureau of Surrealist Inquiries was opened at 15 rue de Grenelle, Paris, in October 1924. ‘The Bureau of Surrealist Inquiries is engaged in collecting, by every appropriate means, communications relevant to the diverse forms which the unconscious activity of the mind is likely to take.’ The general public were invited to the Bureau to confide their rarest dreams, to debate morality, to allow the staff to judge the quality of those striking coincidences that reveal the arbitrary, irrational magical correspondences of life.

~ Angela Carter, “The Alchemy of the Word”

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized

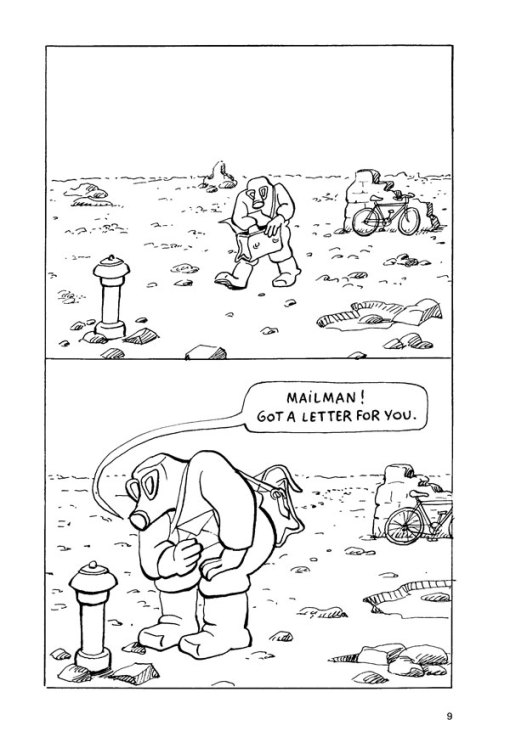

Postapocalyptic Postmen (non-Brin)

22 01 2010I’m awfully late with this (it’s been live since the year turned, more or less, but I’ve only just gotten ’round to publicizing), but better late than never: a bit of science fiction in translation, an excerpt from the graphic novel Letter to Survivors, a comic by the inimitable Gébé rendered by yours truly, up at Words Without Borders. I did another Gébé piece in WWB last fall, and I’m terrifically fond of the author, his whimsy, wit, and pained humanism.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized

Slowly, Through Select Testimonies

23 12 2009to its advent–for example, here and here–a book long merely dream or rumor is becoming printed fact:

“Then English and French and mere Spanish will disappear from the globe. The world will be Tlön.” ~ J.L.B.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : advertising, Chateaureynaud, Edward Gauvin, Translator, fiction, French, plug, promotional, Translation, translator, Uncategorized

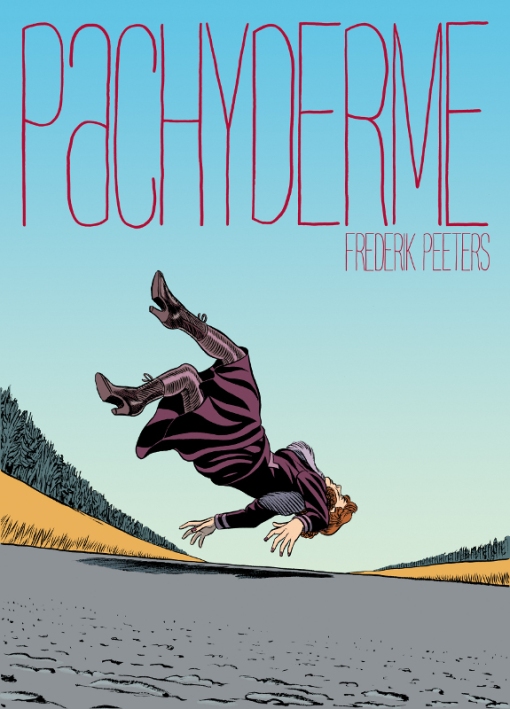

Peeters’ Pachyderme

17 11 2009From my recent review of Frédérik Peeters’ Pachyderme:

Let’s see… in the breathless opening to this 90 page graphic novel we get a traffic jam due to a wounded elephant; a blind pigkeeper; a gray hydrocephalic baby—vaguely alien-looking—in the woods; a cavalier and alcoholic skirt-chasing surgeon; and a beanpole of a Swiss secret policeman, complete with trenchcoat, stovepipe hat, and prosthetic proboscis, who like Get Smart’s Agent 13 turns up in the unlikeliest of places. A woman—our heroine Carice—walks though it all—from her car through the woods, as if in a trance, to a hospital to visit her diplomat husband, indisposed from an auto accident. Her goodbye note, which she intends to deliver in person, is in her purse. The hospital is vast, remote, and forbidding, filled with suitable loonies. Among those Carice meets in the lobby are a paraplegic who offers to help hide her if she’s a Jew, and an orderly who insists she’s come for the annual show patients put on. The secret policeman insists she see the Don Juan of a doctor before her husband, because the former has a file that should be in the latter’s hands: a file valuable to the Soviets, detailing activities of the Red Cross. The book’s first third ends with Carice waking an apparently dead body in the morgue with her whistling. Chopin? the body asks. Carice nods. We learn of her too-early marriage, her dashed dreams as a concert pianist, and in the course of conversation realize that the aged cadaver she’s talking to is her future self.

Read the rest at Absinthe Minded!

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized

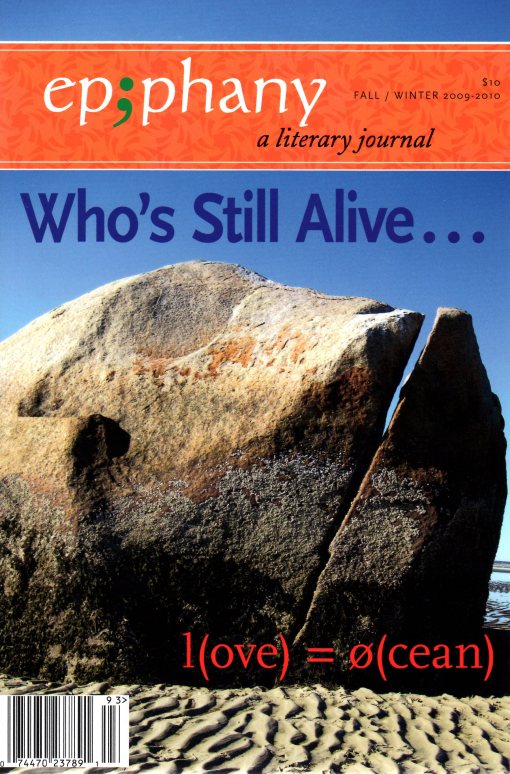

Epiphany, Fall 2009 Issue Now Available

15 11 2009for purchase online and at purveyors of discerning periodicals near you. Die not for lack of what is found in poems, difficult as it may be to get the news from them.

Featuring H.V. Chao’s short story “Jewel of the North” and Edward Gauvin’s translation of Georges-Olivier Chateaureynaud’s “Talking Ape Clobbered by Clowns” amidst a host of superlative contributors!

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Uncategorized